Potable Water Reuse Report

/in NewsSource: https://rewater.usc.edu/potable-water-reuse-report-ows/

Published by the University of Southern California ReWater Center in collaboration with Trussell

Special Issue

24 November 2025

Onsite Water Systems: An Expanding Reuse Paradigm

Key Takeaways:

- The growth of onsite water reuse (OWR) is clear: 19 US states have regulations or guidelines that allow the practice

- An onsite water system is a decentralized system that collects, treats, and reuses water at the property where it is generated, rather than sending it to a centralized facility

- Stakeholders interviewed for this issue view OWR as an additional tool to support reuse and conservation goals

- Drivers for OWR include: (1) water scarcity, (2) lack of centralized wastewater capacity, and (3) economic advantages

- Key challenges for implementation include: (1) cost, (2) lack of public health requirements and program organization, and (3) stepping out of the “municipal mindset”

- Top solutions to address challenges: (1) legislation and regulations, (2) mandates and incentives, and (3) experience

- The rapid development of OWR across the US shows that the practice is moving into the mainstream

Introduction

Previous issues of the Potable Water Reuse Report have focused on municipal-scale systems, but onsite water reuse (OWR) is emerging as an important new tool in the water resources toolbox. The goals of this issue are to (1) introduce readers to the practice of OWR, (2) describe the growth of OWR in the US, and (3) explain the key drivers, challenges, and solutions for more widespread and safe implementation. While the specific topic of this issue is OWR, the lessons learned from this emerging field are relevant for the pursuit of any new water paradigm—centralized or decentralized, potable or non-potable.

1) What is an Onsite Water System?

An onsite water system is a decentralized system that collects, treats, and reuses water at or near the property where it is generated, rather than sending it to a centralized facility. Two key differentiators with centralized reuse are (1) the fact that onsite water systems are often private (rather than municipal) systems and (2) they are smaller in scale. At its smallest scale, OWR could be a single appliance, such as a recirculating shower or washing machine. The reuse of graywater at a single-family home for irrigation is also considered OWR. To date, the most common implementation of OWR is at building scale, such as a system that collects wastewater from a multi-story commercial building to be treated and reused for toilet flushing and irrigation. At its largest form, multi-building district-scale OWR may collect and reuse 400,000 gpd or more of water for multiple end uses.

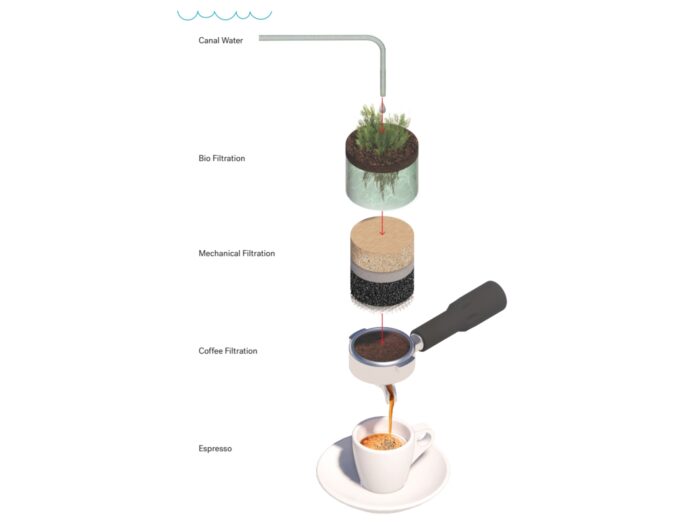

Perhaps the most unique aspect of OWR (versus centralized water reuse) is the multiple combinations of source waters (i.e., where the water is coming from) and end uses (i.e., where the water goes after treatment). Source waters span a range of qualities from relatively clean roof runoff to onsite wastewaters (typically blends of both blackwater from toilets and kitchen sinks and graywater from bathroom sinks, showers, washing machines, etc.). Onsite wastewaters may be of higher strength than municipal-scale sewage. End uses have primarily focused on non-potable applications (e.g., toilet flushing, irrigation), though there is growing interest in “near-potable” applications (e.g., showering) and even potable reuse. Figure 1 shows the different scales of OWR as well as the source waters and end uses typically associated with each scale. Generally, larger scales of OWR allow a greater diversity of source waters and end uses.

OWR is not restricted to civilian applications but is also used in military operations. For example, forward operating bases may use an onsite water system that collects graywater and reuses it for toilet flushing, clothes washing, and showering. Stateside field training bases have also benefited from various types of OWR.

2) How does OWR fit into other centralized efforts for reuse?

It is well known that centralized reuse benefits from economies of scale—large volumes of water can be collected, treated, and distributed for widespread reuse, which can drive down the overall cost of the water. That said, centralized reuse also relies on investment to build and maintain vast collection and distribution systems. When implementing centralized non-potable reuse (NPR), a separate and large-scale conveyance system is needed to distribute the water. The cost of this infrastructure has been a key driver for municipal potable reuse—because potable reuse projects meet drinking water standards, they can take advantage of existing potable water distribution systems. OWR provides another way to avoid expansive and costly infrastructure by reusing the water in the same location that it is collected.

But it is not appropriate to set up a dichotomy between onsite and centralized reuse: OWR is best implemented as one part of an overall reuse/conservation strategy. To maximize reuse, a community likely needs to rely on multiple strategies. Limitations for centralized systems often create opportunities for decentralized options. Paula Kehoe, Director of Water Resources at San Franciso Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC), described how San Francisco uses onsite water systems as an important solution in a broader portfolio of water supply options. San Francisco’s geography and existing infrastructure has driven their reuse implementation approach, with centralized NPR on the west side of the city—which has more parks and single-family homes—and OWR in the east side’s urban center where the development of new buildings provides an opportunity to install decentralized water systems.

3) A growing field…with growing pains

OWR is rapidly growing across the US as evidenced by the 19 states that have developed regulations or guidelines for the practice. A key challenge with growth, however, is the need to address knowledge gaps and create consistency. One organization that has been instrumental in advancing the field over the last decade is the National Blue Ribbon Commission (NBRC) for Onsite Water Systems. The NBRC is composed of representatives from public agencies and institutions, including local and state public health regulators, and staff from water utilities, wastewater utilities, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the US Army Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC). The NBRC has focused on identifying challenges and developing solutions to promote the safe implementation of onsite water systems (see subsequent sections for further discussion).

One of the first priorities tackled by the NBRC was to develop consistent OWR treatment goals that protect public health. In 2017, the NBRC convened an expert panel to develop a risk-based regulatory framework for OWR, providing clear treatment goals in the form of pathogen log reduction targets (LRTs). Before LRTs were developed, OWR treatment technologies provided inconsistent levels of treatment. By defining LRTs, the industry clarified the minimum level of treatment required for public health protection.

While the initial 2017 version of LRTs was a key milestone, multiple entities, including California’s State Water Resources Control Board Division of Drinking Water (DDW) and the EPA, continued to evolve and update the risk-based analysis to further refine the LRTs. Though all are protective of public health, these updates have led to multiple—and different!—LRT goals, depending on the assumptions used. Figure 2 shows three LRT alternatives for treating onsite wastewater and reusing it for toilet flushing based on LRT development conducted by DDW (Alternative 1) and the US EPA (Alternatives 2 and 3).

Despite having alternative LRTs, a system that uses a membrane bioreactor (MBR), UV disinfection, and free chlorine disinfection offers a treatment configuration that meets all required LRTs. This consistency in treatment design allows practitioners to move forward even with different LRT alternatives (Figure 2).

4) Drivers, challenges, and solutions for expanding implementation of OWR

While OWR is in its nascent and growing phase, it offers a unique opportunity to gain insight into the process of advancing a new water paradigm. For this issue, interviews were conducted with multiple stakeholders that have been instrumental in bringing the field to where it is today. Utility staff, regulators, researchers, system providers, and academics were asked about the drivers, challenges, and solutions for expanding the impleme-ntation of OWR. Figure 3 shows the location and title of each stakeholder interviewed.

Drivers for OWR

The most highly cited drivers for OWR were: (1) water scarcity, (2) overburdened centralized wastewater facilities, and (3) economic advantage. These drivers generally applied across the entire US but some were more relevant in specific geographies.

Water Scarcity. The most highly cited OWR driver in the US West and Southwest was water scarcity. A principal benefit of an onsite water system is that it supports conservation efforts by decreasing potable water demand. Kehoe noted that SFPUC’s pursuit of OWR sprang from their recognition that the most cost-effective way to improve their water supply portfolio was to reduce demand. At the state level, California’s pursuit of statewide OWR regulations was also spurred by the need to address threatened supplies and to increase water resilience, according to Sherly Rosilela. Similarly, Katherine Jashinski recounted how Austin Water (Texas) developed a long-range water resource plan after suffering through a multi-year drought and identified OWR as a key strategy to diversify their portfolio. David Sedlak called OWR “the next step in the conservation journey.”

Water scarcity is not limited to fixed locations but is also a concern when moving people into areas with no existing supplies. For example, water represents a logistical burden for the military’s contingency operations and field training areas since it often needs to be continuously resupplied to meet demands. Consequently, OWR also provides an opportunity for “increasing mobility and reducing resupply intervals” by providing point-of-need production, said Chris Griggs. The small scale of onsite water systems makes them easier to deploy because they can be containerized (e.g., a treatment system can be fully housed in a shipping container), said Martin Page. Eberhard Morgenroth noted that the speed with which OWR can be implemented was a key advantage given that large, centralized infrastructure projects may require decades to implement.

Figure 3: The multiple stakeholders from the US and abroad who were interviewed for this Potable Water Reuse Report issue.

Overburdened Centralized Wastewater Facilities. Interviews identified the lack of wastewater capacity at centralized facilities as a key driver on the US East Coast. Overburdened municipal facilities cause envi-ronmental discharge issues if they cannot fully treat flows entering the facility. This is particularly challenging during storm events in cities that have combined stormwater and municipal sewers. Several locations have incentivized the development of OWR to help prevent combined sewer overflows (CSOs) and to improve the quality of receiving waters. One key project in New York City is the Domino Sugar Factory Redevelopment Project, described Zach Gallagher. It includes a 400,000 gpd (~1.5 million liters per day) district-scale reuse project that collects wastewaters from five new buildings to produce non-potable water for toilet flushing, irrigation, and cooling towers. Any excess water that is not used is discharged to the East River. By providing a high level of onsite treatment, the project simultaneously diverts wastewater from downstream treatment facilities while reducing potable demands. Aaron Tartakovsky cited OWR projects in Connecticut that help protect sensitive environmental zones by reusing significant amounts of wastewater and discharging only a fraction of the highly treated effluent to the environment.

Economic Advantage. OWR can only be sustainable if the communities implementing it see that its benefits outweigh its costs. In many locations, OWR may notbe more cost-effective than centralized treatment. However, interviewees cited several factors that can help tip the scale towards economic viability including (1) high costs of centralized water/wastewater services, (2) infeasible expansion costs for centralized facilities (i.e., treatment and collection/distribution systems), and (3) incentives to address constraints like limited wastewater capacity. Jay Garland cited life-cycle assessments that have identified cases where OWR makes more economic sense because it avoids the costs of constructing an extensive distribution system and pumping water over long distances. Sedlak noted that his initial skepticism of the economic viability of OWR was turned around by techno-economic analyses that demonstrated its lower cost compared to centralized non-potable reuse, particularly when multiple benefits could be achieved. For example, Eawag’s Circular Sanitation Toolbox helps identify opportunities to couple OWR with the recovery of other resources.

Challenges for OWR Implementation

Any new water paradigm faces challenges as it goes through initial implementation and wider adoption. In the interviews, the most cited challenges were: (1) cost, (2) lack of public health requirements and program organization, and (3) the need to step out of the “municipal mindset.”

Cost. The cost of OWR was the primary challenge cited by interviewees. As Michael Jahne explained, “Economies of scale are real!” In practice, an onsite water system can have a higher cost for a developer than a sewer connection to a centralized facility. Both he and Page noted that these calculations, however, should also factor in the added resilience that OWR can bring to a community. One of the biggest challenges is therefore to help potential developers and communities understand when and where OWR can offer significant benefits. One new tool that is helpful for evaluating this trade-off is the EPA’s Non-Potable Environmental and Economic Water Reuse calculator (NEWR), which allows users to evaluate the full cost of both centralized and decentralized reuse including the costs of pumping and distributing water. Gallagher also referenced a combined cost of water and wastewater of $12 per 1000 gallons ($3.20 per 1000 L) as a rule-of-thumb for identifying areas where OWR makes more financial sense. Morgenroth suggested that it’s not appropriate to only look at the cost of water reuse against today’s prices; they should also be compared against future prices: “If you have plenty of water, you may not consider water reuse…until the day you run out of water.”

Lack of Program Organization and Public Health Requirements. Getting OWR off the ground in a new location is often impeded by the absence of a clear and simple permitting pathway. Without a well-structured OWR program, a developer may need permission from multiple, independent city departments, who in turn may have no mechanisms to coordinate with each other. Regulatory reform is often required to break down the bureaucratic obstacles and streamline OWR implementation.

Furthermore, one unique challenge with OWR is that different LRTs are needed to address the wide range of potential source waters and end uses (Figure 1). This leads to a more complex matrix of requirements compared to municipal reuse. This complexity may present challenges for regulators, particularly in regions with insufficient staffing, experience, or internal support to implement a new paradigm.

Stepping Out of the Municipal Mindset. One broader question that came up during multiple interviews was whether the mindset used in municipal settings should carry over into OWR (i.e., design principles, monitoring strategies, etc.). In some cases, this may be beneficial, expressed Garland, such as the application of risk-based LRT frameworks used in municipal settings. But there is not consensus on whether OWR should use the same technologies, design philosophy, and operations approach. Morgenroth questioned whether onsite water systems should look like miniature versions of centralized facilities or if design approaches should be adapted for OWR’s unique constraints. Instead of pushing technologies to their limits while relying on significant operational oversight, he suggested that keeping operations simple (e.g., operating at lower membrane flux rates to extend maintenance intervals) might be favorable for onsite water systems. Griggs agreed, saying that if an onsite water system does not have the same level of operational oversight as municipal-scale systems, then it should be designed to operate with more autonomy and greater robustness against failures. Jahne asked if it made sense to require municipal-scale monitoring technologies at smaller scales, such as in single-family homes. Given the increasing challenges of oversight at decreasing scales, it may be preferred to reduce the monitoring burden and rely on greater levels of treatment to protect public health.

Solutions to Expand OWR Implementation

Several solutions were identified to expand OWR implementation. The most cited solutions were: (1) legislation and regulations, (2) mandates and incentives, and (3) experience.

Legislation and Regulations. Streamlining the permitting process is one of the most critical steps to expand OWR implementation. To do this, San Francisco passed regulatory reform legislation that helped organize the relevant permitting agencies under a single OWR program umbrella. This created clear, cohesive permitting pathways and eliminated the need for developers to coordinate with multiple, independent agencies. San Francisco’s ordinance provided the necessary scaffolding to do OWR more efficiently by improving communication and consistency between the regulators, city officials, trades, and developers, stated Tartakovsky. The NBRC developed model legislation that has facilitated the development of programs across the country, including one for Austin Water.

Beyond legislative reform, the development of uniform public health requirements creates consistency in project implementation by setting the bar for success. The establishment of pathogen LRTs (described above) was cited by multiple interviewees as a key effort by the NBRC to help regulators define public health requirements and create consistency across the nation. While regulations set the bar, they should also include oversight to make sure that the bar is met. Jashinski emphasized the importance of ongoing monitoring to ensure treatment systems function as they were designed. For example, requiring flow meters can ensure that projects comply with their recycled water production goals and allow regulators to identify facilities that are using excess potable water. This oversight motivates projects to maintain their systems and ensure proper operation.

Mandates and Incentives. Several interviewees cited mandates that require the development of OWR as the most effective tool for advancing implementation. Mandates have been used to spur the advancement of OWR in multiple locations across the US including: Austin, TX, which requires condensate and rain water reuse for all buildings over 250,000 square feet; the City of Los Angeles, which requires buildings over 25 stories tall to use recycled water for cooling towers; and the City and County of San Francisco, which requires recycling wastewater in new commercial and graywater in new multi-family buildings over 100,000 square feet.

Financial incentives were also important to kick-start early adopters. Sedlak noted that new paradigms always include a period of experim-entation where the successful ideas are separated from the dead-ends. State and federal funding incentives can be important mechanisms to de-risk projects and convince early adopters to pursue an unproven approach. One such example is New York City’s $4 million investment in Domino Sugar’s $12-16 million redevelopment project, noted Gallagher.

Thoughtfully Implementing a New Paradigm

San Francisco implemented its OWR program in a deliberate, step-by-step approach that has provided a template for other locations. The success has been attributed to three key decisions:

- Non-potable first: In non-potable reuse, the associated risks are lower since people are not directly ingesting the water. The focus for protecting public health is on the control of pathogens. In contrast, potable reuse requires the control of both pathogens and chemicals.

- Start with voluntary involvement: participating in San Franciso’s program was initially voluntary. This provided a smaller roll-out that tested the regulatory framework and allowed time for system owners, designers, and regulators to gain experience. When the program became mandatory, the stakeholders involved were more prepared because they benefitted from lessons learned during the voluntary roll-out.

- Multi-story building scale first: the professional management of larger buildings (>250,000 sf)can facilitate the operation and maintenance of onsite water systems. In contrast, OWR in single family homes relies on the homeowner to maintain the system. Larger buildings also allow for greater economies of scale. For example, wastewater could be collected and treated onsite for reuse in hundreds of toilets throughout a large building.

Experience. Experience helps to reduce the risk of a new paradigm by providing confidence in the effectiveness of a given approach (see callout box). New paradigms are often characterized, however, by a lack of experience! Morgenroth recommended starting slowly and providing a safety net to test new OWR applications. This could include access to a potable water supply and a sewer connection to serve as a back-up plan in the event of an onsite water system failure.

Rosilela highlighted DDW’s multi-decade experience with centralized reuse as valuable background for the development of statewide OWR regulations. As the lead for OWR regulatory development and adoption in California, Rosilela leveraged her own multi-year experience with the State Water Board’s Recycled Water Unit and the Division of Water Quality. Similar to California, regulators elsewhere can rely on their experience with municipal-scale reuse to inform regulations for OWR. That said, Sedlak recommended not jumping into regulations too quickly without experience, saying that an initial period of experimentation is critical to figure out what works.

Tartakovsky noted the importance of successful marquee projects to provide concrete proof that OWR can be done well, adding, “People want to be first to be second.” He believes that an initial, successful project can help destigmatize the practice and bring it into the mainstream. Griggs echoed similar sentiments about the Army’s onsite water system that will be installed at the National Guard headquarters in Arlington, VA. It will be a valuable opportunity to demonstrate that the onsite water system can reduce energy use while recovering and reusing 80% of the water. Such demonstrations are key for developing traction and proving OWR’s viability.

5) Moving Forward

The newest water reuse paradigm in the US right now is OWR. From civilian to military applications, appliance-scale to district-scale, using sources as varied as roof runoff and wastewater, OWR is an additional tool that can offset potable demands and reduce the burden on centralized infrastructure. As the newest kid on the reuse block, the OWR industry is growing rapidly as it gains broader experience and tailors its approach to the unique constraints of the decentralized scale. The rapid development of statewide and local OWR regulations shows that the practice is moving into the mainstream across the US.

As OWR moves forward, stakeholders are voicing an interest in expanding from strictly non-potable applications (e.g., toilet flushing and irrigation) to near-potable (e.g., showering) and even potable uses. Because these applications result in higher levels of exposure to users, they require greater levels of treatment and oversight for both pathogen and chemical control. An important benefit of additional end uses, however, is the opportunity for even higher levels of reuse compared to non-potable applications alone.Potable reuse would also remove the need for dual-reticulation plumbing, eliminating a costly element of non-potable OWR and further reducing the cost of water. On the other hand, it would also introduce important permitting constraints given that the EPA requires a public water system permit for any system that regularly supplies water to at least 25 people for at least 60 days per year. If the practice of onsite potable reuse is allowed, it may subject onsite water systems to an even higher degree of regulatory oversight.

The practice of OWR is not limited to the US and many interviewees noted that there could be an even greater role for OWR internationally. Tokyo, for example, has a long history of OWR as a means to reduce demand and offset the cost of pumping water into and out of the megacity. OWR is also highly relevant in low- and middle-income countries lacking centralized water infrastructure. In light of this global potential, the NBRC recently launched a new, international initiative called Building Infrastructure Locally for Decentralized Water Systems (BILD) that involves a broad set of stakeholders (e.g., academics, design consultants, product manufacturers, regulators, government officials) to drive further growth and implementation of OWR. The full potential of this field will be worth following!